- Intro

- Persistence (Conceptually)

- Java and Compilation

- Make

- Files and Directories in Java

- Serializable

- Exercise: Canine Capers

- Testing

- Submission

- Mandatory Epilogue: Debugging

- Tips, FAQs, Misconceptions

- Credits

Intro

The goal of this lab is to prepare you for success on Project 2: Gitlet. In this lab, you will learn:

- How to run Java from the command line and run the tests for Capers (the tests for Gitlet are very very similar).

- How to work with files and directories in Java.

- How to serialize Java objects to a file and read them back later (also called Persistence).

So far in this class, you have exclusively made programs whose state only persists while the program is running, and all traces of the program disappear once the program exits. For example, in Project 0, you created a game that you could play while the program was running, but there was no way to save the game state, quit the program, go do some other stuff, and then run the program again, load up your previous progress, and continue playing the game. In this lab, we will go over two methods to make the state of your program persist past the execution of your program: one through writing plain text to a file, and the other through serializing objects to a file. This will be directly applicable to Project 2 Gitlet as well as any future projects you want to do where you want to be able to save state between programs (like Project 3).

As always, you can get the skeleton files with the following command:

$ git pull skeleton master

There’s a lot of background info to get started with this lab. The actual task starts in the section labeled “Exercise: Canine Capers”. However, it’s important to carefully read and do all the sections of the lab that precede this exercise, otherwise it won’t make any sense.

Persistence (Conceptually)

As noted above, all of the programs you’ve written in this class have had no capability to remember anything about their prior executions. For example, when you ran 2048, there was no ability to save your progress to be resumed at a later date.

By contrast, many real world programs out there have the ability to maintain a state that persists across multiple executions. For example, consider the git version control tool. For example, when you call git add, git makes a note of which files you’d like to add.

$ git add Hello.java Friends.java

If you then enter git status, the correct files will be listed:

$ git status

Changes to be committed:

(use "git restore --staged <file>..." to unstage)

modified: Hello.java

modified: Friends.java

Git is able to do this even though the program completely terminates in between these two commands. In other words, if you run git add, then turn your computer off entirely for a year, then come back later, git status will still somehow do the right thing. Git is somehow exhibiting persistence.

The key idea that makes this possible is to use your computer’s file system. By storing information to your hard drive, programs are able to leave information for later executions to utilize.

Important note: Static variables do NOT persist in Java between executions. When a program completes execution, all instance and static variables are completely lost. The only way we can maintain persistence between executions is to store data on the file system.

For the next several sections, we’ll go over a lot of command line and file system knowledge that you’ll need to complete lab 6 and project 2. Some of it may be review for some of you, but we still encourage you to read the entire thing.

Java and Compilation

A walkthrough of “Java Compilation” and “Make” can be found here. The video simply goes over the steps listed in the spec, so if you find yourself confused on the directions then check it out.

Up until now, we have been running our Java code on IntelliJ by clicking

the magic green button. Perhaps surprisingly, there are other more primitive

ways of running Java code that aren’t graphical. What we’re

referring to here is compiling and running Java code through the command line

(your terminal). You may be used to this idea from CS 61A, where we often ran code directly from terminal using python3 myprogram.py.

The Java implementations we use compile Java source code, written by

the programmer in a .java file, into Java .class files containing Java byte code, which may then be executed by a separate program. Often, this separate program, called java, does a mix of interpreting the class file and compiling it into machine code and then having the bare hardware execute it.

We’re going to walk through how to compile and run a .java file from just

your terminal. In order for this all to work, ensure that the following are both

version 15 or above:

$ javac -version

$ java -version

NOTE: If you’re in Windows, make sure that you’re using a Bash prompt. That is, if your terminal starts with “C:", you’re in the wrong kind of terminal window. Open up git bash intead.

If they aren’t, please redo the relevant part from lab1setup.

First ensure your current working directory is sp21-s***/lab6/capers.

These commands will take you there:

$ cd $REPO_DIR

$ cd lab6/capers

While you’re here, go ahead and run the ls command. You’ll see all the

capers files, but the one we want to focus on is a file called Main.java.

To compile the source file and all of its dependencies, run this command within your terminal:

$ javac *.java

The *.java wildcard simply returns all the .java files in the current directory. Run ls again, and you’ll see a bunch of new .class files, including Main.class. These files constitute the compiled code. Let’s see what it looks like.

$ cat Main.class

That command will print out the contents of the file. You’ll see mostly garbage

with many special characters. This is called bytecode, and even though it looks foreign to us, the java program can take this compiled code and actually interpret it to run the program. Let’s see it happen:

$ java Main

Oops! We got an error.

Error: Could not find or load main class Main

Caused by: java.lang.NoClassDefFoundError: capers/Main (wrong name: Main)

If we were to translate this error to English, it’s saying “I don’t know what

Main you’re talking about.” That’s because Main.java is inside a package,

so we must use it’s fully canonical name which is capers.Main. To do this:

$ cd .. # takes us up a directory to sp21-s***/lab6

$ java capers.Main

And now the program finally runs and prints out

Must have at least one argument

The lesson: to run a Java file that is within a package, we must enter the

parent directory (in our case, lab6) and use the fully canonical name.

One last thing about command line execution: how do we pass arguments to the

main method? Recall that when we run a class (i.e. java Main), what really

happens is the main(String[] args) method of the class is called. To pass

arguments, simply add them in the call to java:

$ java capers.Main story "this is a single argument"

As demonstrated, you can have a space in one of your elements of String[] args

by wrapping that argument in quotation marks.

In the above execution, the String[] args variable had these contents:

{"story", "this is a single argument"}

You’ll be using the String[] args variable in this lab and in Gitlet. Some

skeleton is already provided to show you how it’s done in the main method

of the Main class.

Although we will be using command-line compilation to run and debug our code, we will still be using IntelliJ to make edits to the code. Please open up Lab 6 in IntelliJ by opening the sp21-s***/lab6/pom.xml file.

Open Main.java, and find the line (around line number 40) that looks like:

if (args.length == 0) {

Utils.exitWithError("Must have at least one argument");

}

Immediately below this code add System.out.println("args: " + Arrays.toString(args));, so that the code now reads:

if (args.length == 0) {

Utils.exitWithError("Must have at least one argument");

}

System.out.println("args: " + Arrays.toString(args));

The word Arrays will be in red, so you’ll want to put your cursor on the red word and press alt+enter (or option+enter on a Mac) to import the java.util.Arrays class. Once you’ve done this, try compiling and running the code from the command line (not IntelliJ!) using the commands below:

$ javac capers/Main.java

$ java capers.Main story "this is a single argument"

This time, your program should print out:

args: [story, this is a single argument]

Note: You may notice a bunch of .class files in IntelliJ in the same folder as your code. As you may recall, we did not have such .class files in project 0, project 1, or in previous labs. This is because IntelliJ stores the .class files that it generates in another folder (usually called either out or target).

Make

Unfortunately, using JUnit testing for this lab and project 2 is awkward, so we’re going to use a more sophisticated command line based testing infrastructure to run automated tests for this lab and project 2.

The key reason is that Capers (this lab) and Gitlet (project 2) are both programs that have persistent state, i.e. each time you run them, they “remember” what they did during previous runs of the program. For example, when you call git add, then git status, the git program somehow keeps track of which files were added, even though it completely terminates execution in between the add and status commands.

For example, a test for the status command for Gitlet would need to:

- Run Gitlet’s

Mainclass with theaddargument. - Let your program finish and exit.

- Run Gitlet’s

Mainclass a second time with thestatusargument. - Test that the printed output of the program shows that it correctly “remembers” what happened in the earlier execution of the program.

Another issue that makes testing hard is that the output of Gitlet is complicated. Gitlet tests must be able to parse the printed output of the program, while also testing that various files contain the right contents.

The end result of all of this is that we’ll be using a custom command line testing suite built by Paul Hilfinger and 61B TAs that uses python as the basic engine for verifying program correctness for this lab and in project 2.

The testing suite is executed using a standard unix tool called make. We won’t talk about how to use make in detail. Just know that there are two things that you can use make for:

- Compiling your code by using the

makecommand. - Running the test suite by using

make checkcommand.

In order to use make, you’ll need to follow the brief instructions here to install make. Additionally, you’ll need Python so follow these instructions if you do not already have Python installed.

Once you have make and python installed, let’s see how to use make to compile your code.

You can run make within any directory as long as it’s within lab6 (

i.e. lab6/capers, lab6, lab6/testing), though for simplicity let’s just

stay in the lab6 directory on our terminals). Try typing the following command in your terminal.

$ make

When you run this command, it will compile all of the .java files in your project directory and

place the .class files in the project folder (in our case, the capers

folder). The output will look something like:

"/Library/Developer/CommandLineTools/usr/bin/make" -C capers default

javac -g -Xlint:unchecked -Xlint:deprecation -cp "..::;..;" CapersRepository.java Dog.java Main.java Utils.java

touch sentinel

You don’t need to understand what any of this means, but basically it’s just compiling your files.

To run the test suite, enter:

$ make check

NOTE: If you get an error that looks like “/bin/bash: python3: command not found” or “python3: Permission denied”, see the FAQ at the end of this spec.

make check launches our tests and prints out which ones you passed and

which ones you did not. Initially, you’ll fail all of the tests since you

haven’t completed this lab assignment yet.

There is also a thread way to use make. Specifically make clean will remove all the

.class files and other clutter if it bothers you having so many files in your

project folder. We suggest running this after you’re done testing for the

moment and want to go back to editing your .java files in IntelliJ.

Terminology note: check and clean are known as make targets. You can actually define more targets for make by creating a custom Makefile. Doing so is well beyond the scope of 61B.

If the above command successfully ran (i.e., you are able to see test output), then you’re ready to start the lab! If you did encounter issues regarding not being able to run make, then get assistance from your TA by putting yourself on the lab queue.

We’ll now move onto how to manipulate files and directories in Java.

Files and Directories in Java

Before we jump into manipulating files and directories in Java, let’s go through some file system basics.

Current Working Directory

The current working directory (CWD) of a Java program is the directory from where you execute that Java program. You can access the CWD from within a Java program by using System.getProperty("user.dir"). Examples follow for Windows & Mac/Linux users - they are very similar, just different stylistically.

Windows

For example, for Windows users, let’s say we have this small Java program located in the folder C:/Users/Michelle/example (or ~/example) named Example.java :

// file C:/Users/Michelle/example/Example.java

class Example {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println(System.getProperty("user.dir"));

}

}

This is a program that prints out the CWD of that Java program.

If I ran:

$ cd C:/Users/Michelle/example/

$ javac Example.java

$ java Example

the output should read:

C:\Users\Michelle\example

Note: This Example.java file was just a hypothetical. You will not find it in the lab 6 skeleton.

Mac & Linux

For example, for Mac & Linux users, let’s say we have this small Java program located in the folder /home/Michelle/example (or ~/example) named Example.java:

// file /home/Michelle/example/Example.java

class Example {

public static void main(String[] args) {

System.out.println(System.getProperty("user.dir"));

}

}

This is a program that prints out the CWD of that Java program.

If I ran:

$ cd /home/Michelle/Example

$ javac Example.java

$ java Example

the output should read:

/home/Michelle/example

Note: This Example.java file was just a hypothetical. You will not find it in the lab 6 skeleton.

IntelliJ

Above, we saw how the “current working directory” is the directory that we’re in when we launch a program. You might wonder what the working directory is when using IntelliJ, since we’re not running it from a directory at all, but rather using the IntelliJ GUI.

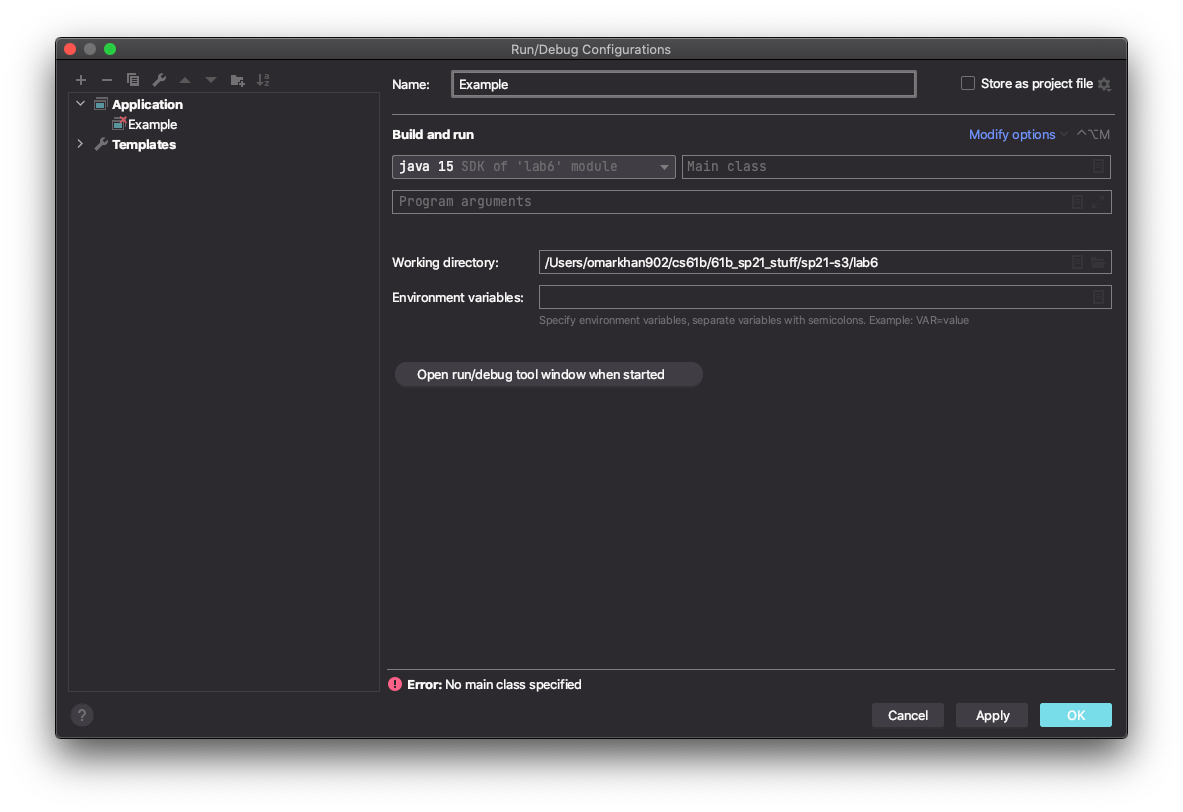

In IntelliJ, the CWD is given by the specified directory under Run > Edit Configurations > Working Directory:

You can see that my CWD is

You can see that my CWD is /Users/omarkhan902/cs61b/61b_sp21_stuff/sp21-s3/lab6. Note that you may have to run Main.java once for this option to appear.

Terminal

In terminal / Git Bash, the command pwd will give you the CWD.

Absolute and Relative Paths

A path is the location of a file or directory. There are two kinds of paths: absolute paths and relative paths.

- An absolute path is the location of a file or directory relative to the root of the file system.

- In the example above, the absolute path of

Example.javawasC:/Users/Michelle/example/Example.java(Windows) or/home/Michelle/example/Example.java(Mac/Linux). Notice that these paths start with the root which isC:/for Windows and/for Mac/Linux.

- In the example above, the absolute path of

- A relative path is the location of a file or directory relative to the CWD of your program.

- In the example above, if I was in the

C:/Users/Michelle/example/(Windows) or/home/Michelle/example/(Mac/Linux) folders, then the relative path toExample.javawould just beExample.java. - If I were in

C:/Users/Michelle/or/home/Michelle/, then the relative path toExample.javawould beexample/Example.java.

- In the example above, if I was in the

Note: the root of your file system is different from your home directory. Your home directory is usually located at C:/Users/<your username> (Windows) or /home/<your username> (Mac/Linux). We use ~ as a shorthand to refer to your home directory, so when you are at ~/sp21-s***, you are actually at C:/Users/<your username>/sp21-s*** (Windows) or /home/<your username>/sp21-s*** (Mac/Linux).

When using paths, . refers to the CWD. Therefore, the relative path ./example/Example.java is the same as example/Example.java.

Similarly, .. refers to the parent (or enclosing) directory. So the command

cd ..

is a quick and simply way to navigate to your parent directory. If you want to go to your parent’s parent directory, you can string these together like so:

cd ../..

And similar for your parent’s parent’s parent directory. You shouldn’t need to do this in this lab/project, though it’s a useful thing to quickly navigate around your terminal.

File & Directory Manipulation in Java

The Java File class represents a file or directory in your operating system and allows you to do operations on those files and directories. In this class, you usually will want to be doing operations on files and directories by referring to them to their relative paths. You’ll want any new files or directories you create to be in the same directory as where you run your program (in this lab, the sp21-s***/lab6 folder) and not some random place on your computer.

Files

You can make a File object in Java with the File constructor and passing in the path to the file:

File f = new File("dummy.txt");

The above path is a relative path where we are referring to the file dummy.txt in our Java program’s CWD. You can think of this File object as a reference to the actual file dummy.txt - when we create the new File object, we aren’t actually creating the dummy.txt file itself, we are just saying, “in the future, when I do operations with f, I want to do these operations on dummy.txt”. To actually create this dummy.txt file, we could call

f.createNewFile();

and then the file dummy.txt will actually now exist (and you could see it in File Explorer / Finder).

You can check if the file “dummy.txt” already exists or not with the exists method of the File class:

f.exists()

Actually writing to a file is pretty ugly in Java. To keep things simple, we’ve

provided you with a Utils.java. This class will be very handy for this lab and

in Gitlet. You should look at the list of available methods in Utils.java to

get a sense of what it can do for you. See the FAQ at the bottom of this lab for

hints on what to focus on.

As an example, if you want to write a String to a file, you can do the following:

Utils.writeContents(f, "Hello World");

Now dummy.txt would now have the text “Hello World” in it.

Directories

Directories in Java are also represented with File objects. For example, you can make a File object that represents a directory:

File d = new File("dummy");

Similar to files, this directory might not actually exist in your file system. To actually create the folder in your file system, you can run:

d.mkdir();

and now there should be a folder called dummy in your CWD. You should also checkout the mkdirs() method, whose documentation can be found here.

Summary

There are many more ways to manipulate files in Java, and you can explore more by looking at the File javadocs and Googling. There are a ton of resources online and, if you Google it, doing more extensive file operations in Java can get a bit complicated. We recommend understanding the basics by doing this lab, and in the future if you come across a use case you don’t know how to handle, then start searching or asking on Ed. For this lab and Gitlet, you should use our Utils.java class that has many useful helper functions for file operations.

Serializable

Writing text to files is great and all, but what if we want to save some more complex state in our program? For example, what if we want to be able to save the Model object in 2048 so we can come back to it later? We could write a toString method to convert a Model to a String and then write that String to a file. However, we’d then have to also write code that is able to read the String and then parse it back into a Model. While it is certainly possible to do so, it’s tedious to write such code.

Luckily, we have an alternative called serialization which Java has already implemented for us. Serialization is the process of translating an object to a series of bytes that can then be stored in the file. We can then deserialize those bytes and get the original object back in a future invocation of the program.

To enable this feature for a given class in Java, this simply involves implementing the java.io.Serializable interface:

import java.io.Serializable;

public class Model implements Serializable {

...

}

This interface has no methods; it simply marks its subtypes for the benefit of some special Java classes for performing I/O on objects. For example,

Model m = ....;

File outFile = new File(saveFileName);

try {

ObjectOutputStream out =

new ObjectOutputStream(new FileOutputStream(outFile));

out.writeObject(m);

out.close();

} catch (IOException excp) {

...

}

will convert m to a stream of bytes and store it in the file whose name is stored in saveFileName. The object may then be reconstructed with a code sequence such as

Model m;

File inFile = new File(saveFileName);

try {

ObjectInputStream inp =

new ObjectInputStream(new FileInputStream(inFile));

m = (Model) inp.readObject();

inp.close();

} catch (IOException | ClassNotFoundException excp) {

...

m = null;

}

The Java runtime does all the work of figuring out what fields need to be converted to bytes and how to do so. You’ll be serializing objects left and right, so to lower the amount of code you have to write we have provided helper function in Utils.java that handles reading and writing objects.

Note that the code above is pretty annoying, with lots of mystery classes and try/catch statements. If you use our helper functions from the Utils class, serializing is as easy as:

Model m;

File outFile = new File(saveFileName);

// Serializing the Model object

writeObject(outFile, m);

And similarly, deserializing is simply:

Model m;

File inFile = new File(saveFileName);

// Deserializing the Model object

m = readObject(inFile, Model.class);

Note: There are some limitations to Serializable that are noted in the Project 2 spec. You will not encounter them in this lab.

Exercise: Canine Capers

Whew! We’re finally read to get started on the actual work for this lab. For this lab, you will be writing a program that will be taking advantage of file operations and serialization. We have provided you with three files:

Main.java: The main method of your program. Run it withjava capers.Main [args]to do the operations specified below. This class doesn’t have too much logic itself: rather, it serves as an “entry point” and simply knows when to call the right method inCapersRepository.javaCapersRepository.java: Handles all coordination among the other classes. The majority of the FIXMEs in this program are in here.Dog.java: Represents a dog that has a name, breed, and age. Contains a few FIXMEs.Utils.java: Utility functions for file operations and serialization. These are a subset of those provided with Gitlet.

You do not need to worry about error cases or invalid input, we aren’t testing you on that in this lab (though beware, you will need to do this for Gitlet). You are able to complete this lab with just the methods provided in Utils.java and other File class methods mentioned in this spec, but feel free to experiment with other methods if you’re feeling adventurous.

Main

Your code will support the following three commands:

story [text]: Appends “text” + a newline (i.e."\n") to a story file in the .capers directory. Additionally, prints out the current story (the current story should include the recently added “text”).dog [name] [breed] [age]: Persistently creates a dog with the specified parameters; should also print the dog’stoString(). Assume dog names are unique.birthday [name]: Advances a dog’s age persistently and prints out a celebratory message.

As an example, below we see a series of executions of capers.Main, followed by the output of each command.

$ java capers.Main story "Once upon a time, there was a beautiful dog."

Once upon a time, there was a beautiful dog.

$ java capers.Main story "That dog was named Fjerf."

Once upon a time, there was a beautiful dog.

That dog was named Fjerf.

$ java capers.Main story "Fjerf loved to run and jump."

Once upon a time, there was a beautiful dog.

That dog was named Fjerf.

Fjerf loved to run and jump.

$ java capers.Main dog Mammoth "German Spitz" 10

Woof! My name is Mammoth and I am a German Spitz! I am 10 years old! Woof!

$ java capers.Main dog Qitmir Saluki 3

Woof! My name is Qitmir and I am a Saluki! I am 3 years old! Woof!

$ java capers.Main birthday Qitmir

Woof! My name is Qitmir and I am a Saluki! I am 4 years old! Woof!

Happy birthday! Woof! Woof!

$ java capers.Main birthday Qitmir

Woof! My name is Qitmir and I am a Saluki! I am 5 years old! Woof!

Happy birthday! Woof! Woof!

Note that the dog and birthday commands have related functionality. Note that the story command has functionality that is entirely independent of dog or birthday.

Also note that your code should NOT print out the command line arguments at each step. In other words, you should delete the call to System.out.println("args: " + Arrays.toString(args)); that you added earlier in this lab.

All persistent data should be stored in a .capers directory in the current working directory. We prepend a . because files and directories preceded by a . are hidden in the file viewer by default. After all, we wouldn’t want the users of our Java program to care about how/where/if we store persistent data. They should only care that the program works. Both IntelliJ and Git take advantage of this idea: whenever you create an IntelliJ project, it creates a hidden .idea folder in the CWD to store all of its metadata. Similarly, whenever you initialize a Git repository, it stores all of its persistent data in a .git folder. You can view hidden files in terminal by typing ls -a instead of just ls.

Recommended file structure (you do not have to follow this):

.capers/ -- top level folder for all persistent data

- dogs/ -- folder containing all of the persistent data for dogs

- story -- file containing the current story

You should not create these manually, your program should create these folders and files (hint: scroll up to see how do we create a directory/file in Java). If you want to remove all saved data from your program, just remove the .capers directory (NOT the capers directory) with rm -rf .capers.

Useful Util Functions

Useful Util functions (as a start, may need more and you may not need all of them):

static void writeContents(File file, Object... contents)- writes out strings/byte arrays to a file. The...allows us to use variable arguments, meaning we can callwriteContentswith any number of arguments. For example, we can callwriteContents(outFile, "dog", "cat", "mouse"), and the functionwriteContentswill have access to all three objects we pass in via an array.static String readContentsAsString(File file)- reads in a file as a stringstatic byte[] readContents(File file)- reads in a file as a byte arraystatic void writeObject(File file, Serializable obj)- writes a serializable object to a filestatic <T extends Serializable> T readObject(File file, Class<T> expectedClass)- reads in a serializable object from a file. You can get aClassobject by using<Class name>.class, (e.g.Dog d = readObject(inFile, Dog.class)).static File join(String first, String... others)- joins together strings or files into a path. E.g.Utils.join(".capers", "dogs")would give you aFileobject with the path of “.capers/dogs”, andUtils.join(".capers", "dogs", "shitzus")would give you aFileobject with the path of".capers/dogs/shitzus". You should not create files by String concatenation! This can create weird bugs depending on the system you are running.

Suggested Order of Completion

Please be sure to read the comments above each method in the skeleton for a description of what they do.

- Fill out

CAPERS_FOLDERinCapersRepository.java, thenDOG_FOLDERinDog.java, and thensetUpPersistenceinCapersRepository.java. - Fill out the

mainmethod inMain.java. This should consist mostly of calling other methods fromCapersRepository. - Fill out

writeStoryinCapersRepository.java. The story command should now work. - Try using the story command manually and verify that it is behaving properly.

- Fill out

saveDogand thenfromFileinDog.java. You will also need to address theTODOat the top ofDog.java. Remember dog names are unique! - Fill out

makeDogandcelebrateBirthdayinCapersRepository.javausing methods inDog.java. You will find thehaveBirthdaymethod in the Dog class useful. The dog and birthday commands should now work. - Try using the dog and birthday commands manually and verify that they are working properly.

- Run make check and verify that you code passes all the tests. If you are failing tests and don’t know why, see the debugging section later in this lab.

Each TODO should take at most around 8 lines, but many are fewer.

Usage

The easiest way to run and test your program is to compile it in terminal with make and then run it from there. E.g.

$ cd $REPO_DIR

$ cd lab6 # Make sure you are in your lab6 folder (NOT the lab6/capers folder)

$ make # or javac capers/*.java, make sure to recompile your program each time you make changes

$ java capers.Main [args] # Run the commands you want! e.g., java story hello

For the story command, if you want to pass in a long string that includes spaces as the argument, you will want to put it in quotes, e.g.

$ java capers.Main story "hello world"

Testing

As discussed earlier, tests are run using the check make target, i.e.:

$ make check

These are the exact tests on Gradescope, so if you pass them locally you should get a full score on Gradescope.

However, you should also do some ad-hoc testing. That looks something like this:

$ make # to compile all your .java files

$ java capers.Main story Hello

Hello # this should be printed

$ java capers.Main story World

Hello # this should be printed

World

$ ls .capers # investigate the .capers folder to make sure it looks how

# you expect

... # More commands + investivgation

Recall we said we aren’t using JUnit tests for Capers nor Gitlet. A single test

is represented as a file with the file extension .in: all of our tests are in

the lab6/testing/our directory. Here is what the test02-two-part-story.in

looks like:

# Two uses of the `story` command

> story "Hello"

Hello

<<<

> story "World"

Hello

World

<<<

The first line is a comment telling us what the test does. If you’re failing a test, you should read the top line to get a sense of what the test is doing.

The next 3 lines make up a section corresponding to a single execution to the program:

> [args given to capersMain.main()]

[first line of expected output]

[second line of expected output]

[...]

<<<

So we see that all of the text on the same line as the > corresponds to the

command given to capers.Main.main(), and the next lines up until the <<< are

the expected output.

So that first section is saying “If I run the program with args story

"Hello", then the program should output Hello.” If your program doesn’t have

the exact same output, then our tests will fail and tell you your output

differs.

With this in mind, let’s make sense of the next section:

> story "World"

Hello

World

<<<

When we run the command capers.Main story "World" after the first capers

command, the output should now be the concatenated story “Hello” followed by a

new-line character then “World”. The word "Hello" is there because of

persistence: even though these are separate executions of the program, your code

should have somehow recorded the fact that "Hello" is part of the story

(likely putting this string in some file).

We call these integration tests. As opposed to unit tests, integration tests test many things in cohesion. A (good) unit test will only test one specific portion of your program: in our integration tests, we test multiple things. You can see from the names of these integration tests that we’ve tried to provide some tests to isolate a particular functionality of capers, so those should help you get started and give you a basic sanity check of your work so far.

Submission

Once you have passed all of the integration tests that are run when you call make check, youa ready to submit. You should have made changes in capers/Main.java, capers/Dog.java, and

capers/CapersRepository.java. Submit the lab as always:

$ git commit -m "<commit message>"

$ git push origin master

And then submit on Gradescope. There is no style check for this lab.

Mandatory Epilogue: Debugging

Before completing this section you should have passed all of the make check tests. You should also have submitted to gradescope. Even though you have your points for the lab, there is one more thing to do.

In this section, we’ll talk about how to use the IntelliJ debugger to debug lab 6. This might seem impossible at first glance, since we’re running everything from the command line. However, IntelliJ provides a feature called “remote JVM debugging” that will allow you to add breakpoints that trigger during our integration tests.

Start by using git to checkout the original version of the skeleton code. That is, after checking out, you should be back right where you started at the very beginning of this lab. If you don’t know how to do that, read this section from Lab 4.

A walkthrough of the remainder of this section of the lab can be found here. The video simply goes over the steps listed in the spec, so if you find yourself confused on the directions then check it out.

Without JUnit tests, you may be wondering how to debug your code. We’ll walk you through how you will do that in Capers and in Gitlet.

First, let’s discuss how you would know you have a bug. If you run the

the make check tests, you’ll see that you’re failing the test

test02-two-part-story.in. Now we need

to figure out which execution of your program was buggy. Remember that our

tests will run your program multiple times; in this case, the .in file has

2 lines that call capers.Main, so this test runs it

twice (though in Gitlet it’ll typically be more than that).

To debug this integration test, we first need to let IntelliJ know that we want to debug remotely.

Navigate to your IntelliJ and open your lab6 project if you don’t have

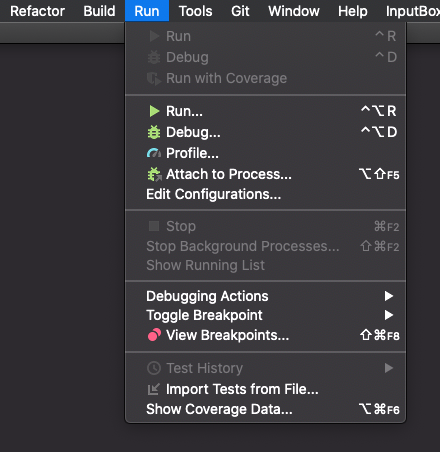

it open already. At the top, go to “Run” -> “Run”:

You’ll get a box asking you to Edit Configurations that will look like the below:

Yours might have more or less of those boxes with other names if you tried running a class within IntelliJ already. If that’s the case, just click the one that says “Edit Configurations”

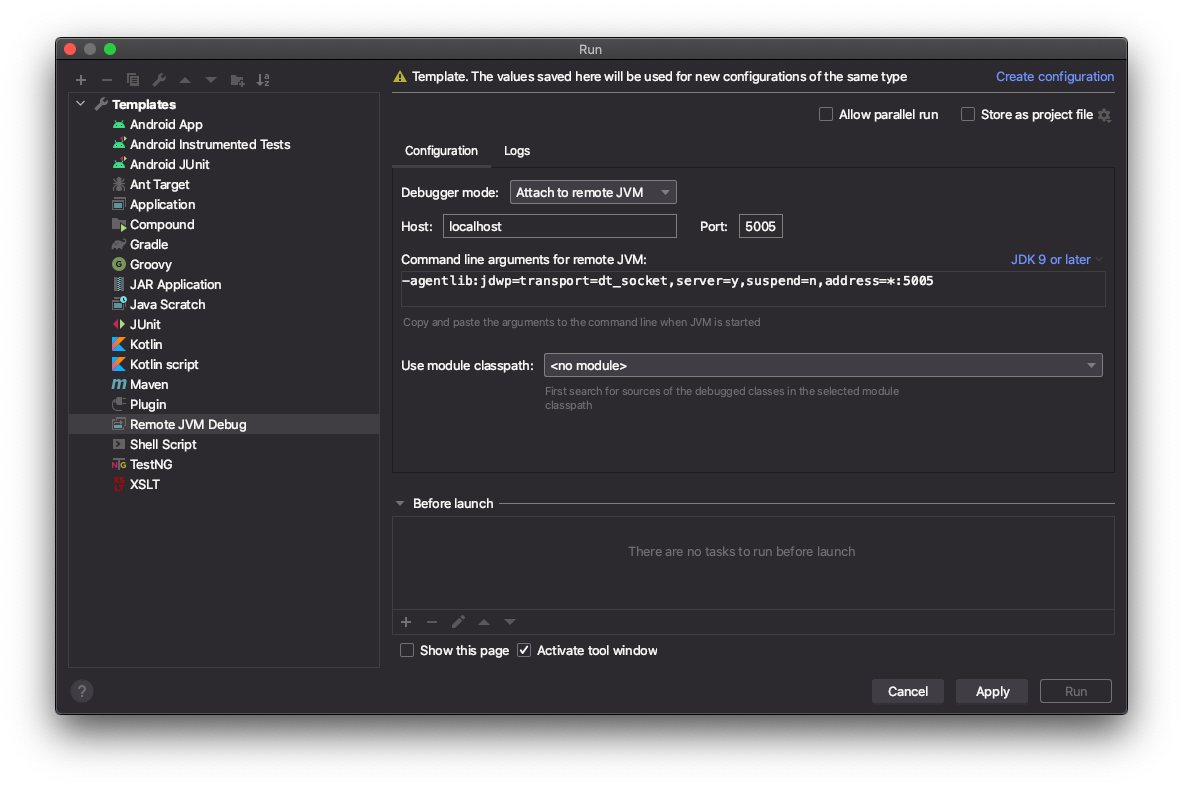

In this box, you’ll want to hit the “+” button in the top left corner and select “Remote JVM Debug.” It should now look like this:

We just need the default settings. You should add a descriptive name in the top

box, perhaps “Capers Remote Debug”. After you add a name, go ahead and hit

“Apply” and then exit from this screen. Before we leave IntelliJ, place a

breakpoint in the main method of the Main class so we can actually debug.

Make sure this breakpoint will actually be reached, so just put it on the first

line of the main method.

Now you’ll navigate to the testing directory within your terminal.

The script that will connect to the IntelliJ JVM is runner.py: use the

following command to launch the testing script:

python3 runner.py --debug our/test02-two-part-story.in

If you wanted to run a different test, then simply put a different .in file.

If you’d like the .capers folder to stay after the test is completed to

investigate its contents, then use the --keep flag:

python3 runner.py --keep --debug our/test02-two-part-story.in

For our example it doesn’t matter what you do; we’ve just included it in case

you’d like to take a look around. By default, the .capers that is generated

is deleted.

If you see an error message, then it means you are either not in the testing

directory, or your REPO_DIR environment variable isn’t set correctly. Check

those two things, and if you’re still confused then ask a TA.

Otherwise, you should be ready to debug! You’ll see something like this:

============================================================================

| ~~~~~ You are in debug mode ~~~~~ |

| In this mode, you will be shown each command from the test case. |

| |

| There are three commands: |

| |

| 1. 'n' - type in 'n' to go to the next command without debugging the |

| current one (analogous to "Step Over" in IntelliJ). |

| |

| 2. 's' - type in 's' to debug the current command (analogous to |

| "Step Into" in IntelliJ). Make sure to set breakpoints! |

| |

| 3. 'q' - type in 'q' to quit and stop debugging. If you had the `--keep` |

| flag, then your directory state will be saved and you can |

| investigate it. |

============================================================================

test02-two-part-story:

>>> capers story "Hello"

>

The top box contains helpful tips. What we see next is the name of the .in

file we’re debugging, then a series of lines that begin with >>> and >.

Lines that begin with >>> are the capers commands that will be run on your

Main class, i.e. a specific execution of your program. These correspond to the

commands we saw in the .in file on the right side of the >.

Lines that begin with > are for you to enter debug commands on. The 3

commands are listed in the helpful box.

Remember that each input file will list multiple commands and therefore multiple executions of our program. We need to first figure out what command is the culprit.

Type in the single character “n” (short for “next”) to execute this command without debugging it. You can think of it as bringing you to the next command.

One of these will error: either your code will produce a runtime error, or your output wasn’t the same. For example:

============================================================================

| ~~~~~ You are in debug mode ~~~~~ |

| In this mode, you will be shown each command from the test case. |

| |

| There are three commands: |

| |

| 1. 'n' - type in 'n' to go to the next command without debugging the |

| current one (analogous to "Step Over" in IntelliJ). |

| |

| 2. 's' - type in 's' to debug the current command (analogous to |

| "Step Into" in IntelliJ). Make sure to set breakpoints! |

| |

| 3. 'q' - type in 'q' to quit and stop debugging. If you had the `--keep` |

| flag, then your directory state will be saved and you can |

| investigate it. |

============================================================================

test02-two-part-story:

>>> capers story "Hello"

> n

ERROR (incorrect output)

Directory state saved in test02-two-part-story_0

Ran 1 tests. 0 passed.

For us, it was our first command. Notice also it tells us Directory state saved

in test02-two-part-story_0 because we had the --keep flag enabled. We could

now investigate that directory to see what happened. If we debugged again with

the --keep flag on the same test, we’ll get a new directory Directory state

saved in test02-two-part-story_1 and so on.

Once you’ve found the command that errors, do it all again except now you can hit “s” (short for “step”) to “step into” that command, so to speak. Really what happens is the IntelliJ JVM waits for our script to start and then attaches itself to that execution. So after you press “s”, you should hit the “Debug” button in IntelliJ. Make sure in the top right the configuration is set to the name of the remote JVM config you added earlier (this is why it is helpful to give it a good name).

This will stop your program at wherever your breakpoint was as it’s trying to run that command you hit “s” on. Now you can use your normal debugging techniques to step around and see if you’re improperly reading/writing some data or some other mistake.

You might get scenarios where the command you’re debugging did everything it was supposed to: in these cases, it means you had a bug on a previous command with persistence. For example: let’s say your second invocation looks like it is doing everything correctly, except when it tries to read the previous story (that should have been persistently stored in a file) it receives a blank file (or maybe the file isn’t even there). Then, even though the second execution of the program has output that doesn’t match the expected, it was really the previous (first) execution that has the bug since it didn’t properly persist the data.

These are very common since persistence is a new and initially tricky concept, so when debugging, your first priority is to find the execution that produced the bug. If you didn’t, then you would be debugging the second (non-buggy) execution for hours to no avail, since the bug already happened.

Debugging will look exactly the same for Gitlet as described in this section. Even though your work for this debugging epilogue is not graded, you should still complete it!

Don’t forget to checkout your lab6 back to your solution and not the skeleton!

Tips, FAQs, Misconceptions

Tips

These are tips if you’re stuck!

setUpPersistence: InsetUpPersistence, you should make sure that if the files and folders you need for the program to work don’t exist yet that they are made.writeStory: You should be usingreadContentsAsStringandwriteContents. It is not sufficient to just usewriteContents, since that method overwrites the file instead of appending to it. Since the story is just plain text (i.e. it’s just a string), you do not need to serialize anything.saveDog: You should be usingwriteObject, since Dogs aren’t Strings so we want to be able to serialize them. Make sure you’re writing your dog to a File object that represents a file and not a folder!fromFile: You should be usingreadObject. This should be similar tosaveDogexcept you’re loading a Dog from your filesystem instead of writing it!

FAQs & Misconceptions

- If make check isn’t working, you may need to add an additional argument when you call

make check. Most computers take the commandpython3in order to run Python. However, on some computers you may need to typepythonorpyto run Python. If this is the case for you, you should use the flag:

$ make check PYTHON=<whatever you use to run Python files>

So if you use py to run Python, then use the command:

$ make check PYTHON=py

If you don’t want to keep adding this extra text to make check every time, you can edit line 25 of the file called Makefile.

writeObject:writeObjecttakes in (1) theFileobject that represents the file you want to write the object to and (2) the object you want to serialize and write into the file. The first argument should be aFileobject that represents a file on your filesystem, not a directory.- File objects can represent both files and directories in your filesystem. The only way to differentiate between them is the methods you use with the File object. You can check if a File object represents a directory with

.isDir(), which you shouldn’t need for the lab since you should already know which File objects represent files and which represent directories. - Creating a new File object in Java does not create the corresponding file or directory on your computer. The file is only created when you call

.createNewFile()ormkdir()on that File object. You can think ofFileobjects as pointers to files or directories - you can have multiple of them, and whenever you want to actually change the corresponding file or directory, you will need to call specific methods (usually the ones inUtilswith “read” and “write” in the name). Utils.join(File d, String s)is shorthand fornew File(File d, String s)(andUtils.join(String d, String s)is shorthand fornew File(new File(d), String s)), both of which will create a new File object that represents the file or folder calledsin theddirectory. Again, this doesn’t make the actual file/folder in your filesystem until you call appropriate methods.- When we say “make changes persistently”, that means you should make the changes in Java and then also make sure that those changes are reflected on your filesystem by writing those changes back into the appropriate files.

Credits

Capers was originally written by Sean Dooher in Fall 2019. Spec and lab adaptation were written by Michelle Hwang in Spring 2020 and then Omar Khan in Spring 2021.